Reviewing anti-microbial resistance

17/02/2021

The UKWIR project Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) began in October 2019, with Thames Water's Howard Brett as Programme Lead and Tony Andrews as UKWIR Project Manager, to review the current research and to try to signpost the possible implications for the water industry.

At the project dissemination workshop Dr Emma Hayhurst from the contractor, the University of South Wales, informed on-line delegates about the findings of the comprehensive literature review they had undertaken.

The review illustrated the complexities of AMR, particularly the behaviour and population dynamics of antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) during and after sewage and sludge treatment.

It highlighted that there was little understanding of the relative contributions of sewage, agriculture and industry to environmental AMR, and the impact of each is likely to be different in each receiving environment.

AMR in the environment

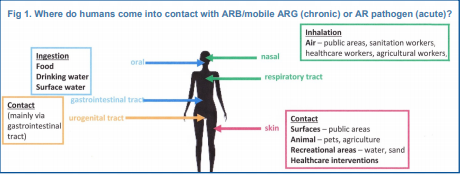

There are many opportunities for environmental AMR to impact on humans, as illustrated in figure 1, although the single most likely exposure route relevant to the water industry in terms of potential regulation is via contact/ingestion in recreational waters.

Wastewater treatment plant effluent and biosolids are recognised as sources of resistant bacteria into the environment, although their subsequent fate is usually unknown.

Furthermore, the treatment processes for both wastewater and sludges can themselves be a selection pressure, particularly if co-selectors such as antibiotics, metals and biocides are present.

Nonetheless, it is clear that wastewater treatment is of very positive benefit in reducing AMR release.

Limited evidence

Emma set out the headline conclusions which included:

- AMR in water, wastewater and soils is a potential public health risk, but direct evidence of this risk is limited. However, employing treatment of any kind is better than no treatment.

- routine environmental monitoring combined with in-depth catchment-scale analysis would increase understanding of the risks posed and possible interventions.

The project report sets out many recommendations including:

- evolutionary risks should be managed globally and locally with support of international efforts to improve basic sanitation

- there is a need to prioritise heavily contaminated areas in the UK and Ireland for in-depth analysis

- understand the role of untreated sewage on environmental burdens of AMR is required

- there should be an In-depth collaborative catchment-level analysis to understand drivers of AMR in the UK and Irish environment

- the impact of hospital/livestock/industrial waste entering sewers needs to be quantified

- control at source campaigns should involve public education as well as working with Health Authorities and agriculture to reduce unnecessary antibiotic consumption.

The results of this project will be fed into a National Chemical Investigations Programme project that UKWIR is project managing. It is investigating AMR as well as assisting regulators and Government in determining what monitoring may be most useful.

UKWIR will consider the recommendation for further research.

Howard Brett said ‘it is essential to understand properly the role and contribution of the water industry to the spread of AMR, and hence if there is justification to develop additional treatment stages to minimise any risks. Our primary role is the protection of public health’.